Optimizing CUDA Shuffles with SCALE

Justine Khoo

Mon Jan 19 2026

Compilation of CUDA shuffles to use AMD's Data-Parallel Primitives (DPP) is a novel and unique compiler optimization in SCALE, first added in version 1.4.2. It's important to be able to execute shuffles efficiently as they are used in virtually all CUDA kernels. Therefore, this compiler optimization is an example of where SCALE can not only solve the problem of CUDA compatibility with AMD GPUs, but also where SCALE can significantly improve performance of existing CUDA code.

DPP is a hardware feature that's unique to AMD GPUs. AMD GPUs have the ability to execute shuffles more efficiently than any other GPU architecture. Our measurements show that DPP on AMD is about 10x faster than shuffles in CUDA. Therefore, existing CUDA programs can be sped up by compiling them with SCALE and running them on an AMD GPU, in turn reducing compute costs or increasing the size of model that can be used for a given amount of compute.

However, DPP has been rarely used in practice. This is because no compiler has previously been able to generate code that uses DPP, so DPP could only be accessed via hand-written assembly code or compiler intrinsics. Every program needing to use DPP would need to be hand-optimized specifically for AMD. But not any more: now SCALE enables all existing CUDA programs to execute shuffles efficiently using DPP (including those programs that use shuffles via inline PTX).

Recap: why shuffles are important in CUDA

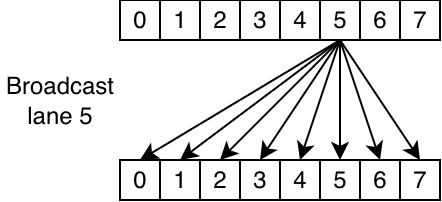

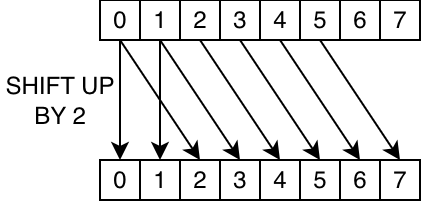

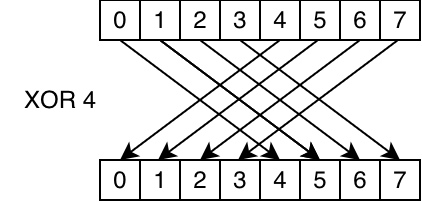

CUDA provides functions such as __shfl to exchange data within a group of threads according to a specified pattern. For example:

__shfl(data, 5, 8): read from lane 5

__shfl_up(data, 2, 8): read from the lane that's two indexes below

__shfl_xor(data, 4, 8): XOR the lane index with 4 to get the source lane

The common but slow way of compiling shuffles: ds_bpermute

Upstream LLVM adopts a correct but overly general (and therefore slow) method when compiling the most commonly-used shuffles for AMD GPUs. We will illustrate this with the following example:

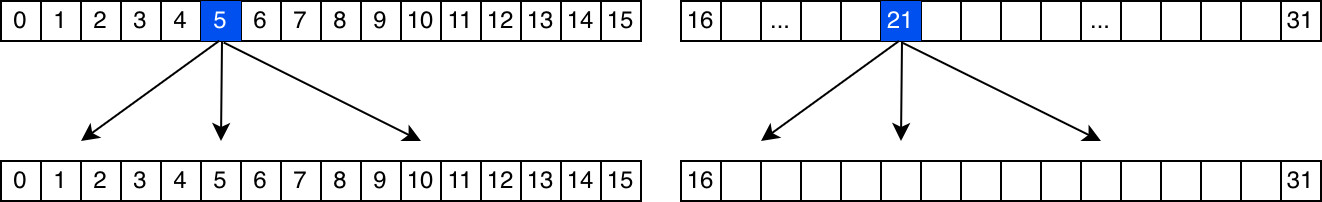

Task: divide the threads into groups of 16, and share the value in lane 5 with its entire group

CUDA: __shfl_sync(~0u, value, 5, 16)

Here is the generated device code (we'll explain the most important part afterwards):

s_load_b128 s[0:3], s[0:1], 0x0

v_mbcnt_lo_u32_b32 v0, -1, 0

v_mov_b32_e32 v2, 0

s_delay_alu instid0(VALU_DEP_2)

v_lshlrev_b32_e32 v0, 2, v0

s_waitcnt lgkmcnt(0)

global_load_b32 v1, v0, s[0:1]

; wave barrier

s_waitcnt vmcnt(0)

ds_bpermute_b32 v1, v2, v1 offset:20

s_waitcnt lgkmcnt(0)

global_store_b32 v0, v1, s[2:3]

s_endpgm

The most important instruction for our purposes is ds_bpermute. In this context, the word "permute" means to copy data between threads in the warp. ds_bpermute can perform an arbitrary permutation across a warp. You simply give it an array src of the same size as the wavefront, where src[i] is the index that lane i will read from.

ds_bpermute is usually more complex than we need, since it can perform any arbitrary permutation between 32 (or 64) lanes. While programmers can make __shfl and friends perform any permutation (by passing in a variable as the source lane), the most common cases are those described above: broadcasts, xors and shifts. While the generated code is correct, the generality of bpermute comes at a cost: it uses the __shared__ memory hardware to do the permutation, giving it a comparable cost to a shared memory read.

Optimizing common types of shuffle: AMD's awesome DPP

The performance of the example above would be significantly improved if the whole computation could be executed while staying within the registers. AMD GPUs have hardware features (including DPP) that can do restricted kinds of permutation an order of magnitude faster. We just need to implement some compiler magic to enable permutations to be compiled to DPP.

DPP is a powerful feature of AMD GPUs which can implement specific patterns of shuffles entirely within the register file. Even better, the permutation can be fused onto the input operand of another instruction, allowing direct access to registers from other lanes when performing many calculations. Using DPP, we've gone from a shuffle needing to access the memory cache, to in many cases being effectively free!

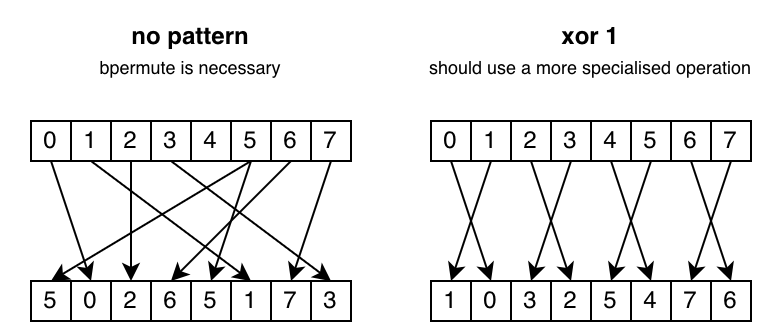

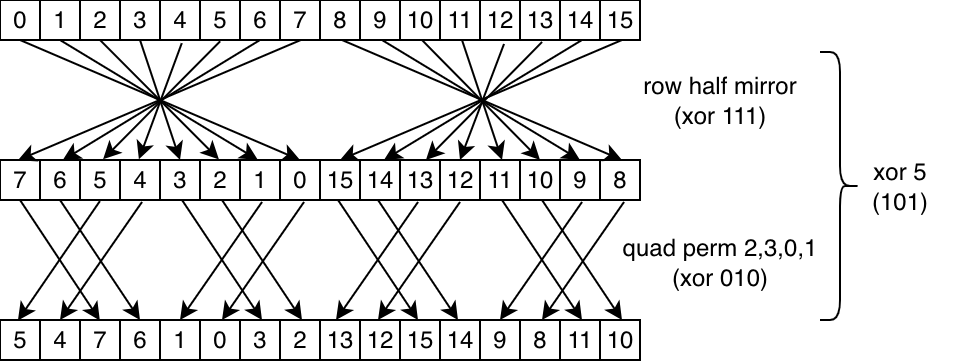

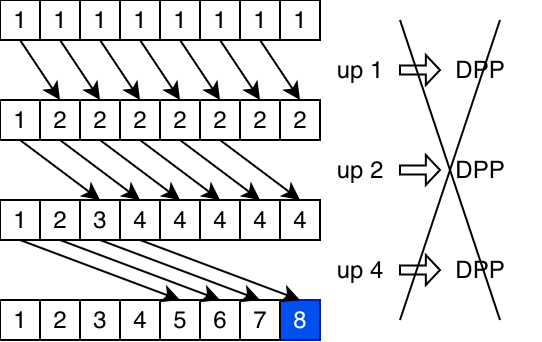

To illustrate the difference between shuffles that need bpermute and shuffles that can be executed using DPP, the following diagram shows a complex example of where bpermute would be necessary, contrasted with a case that can be optimized with DPP:

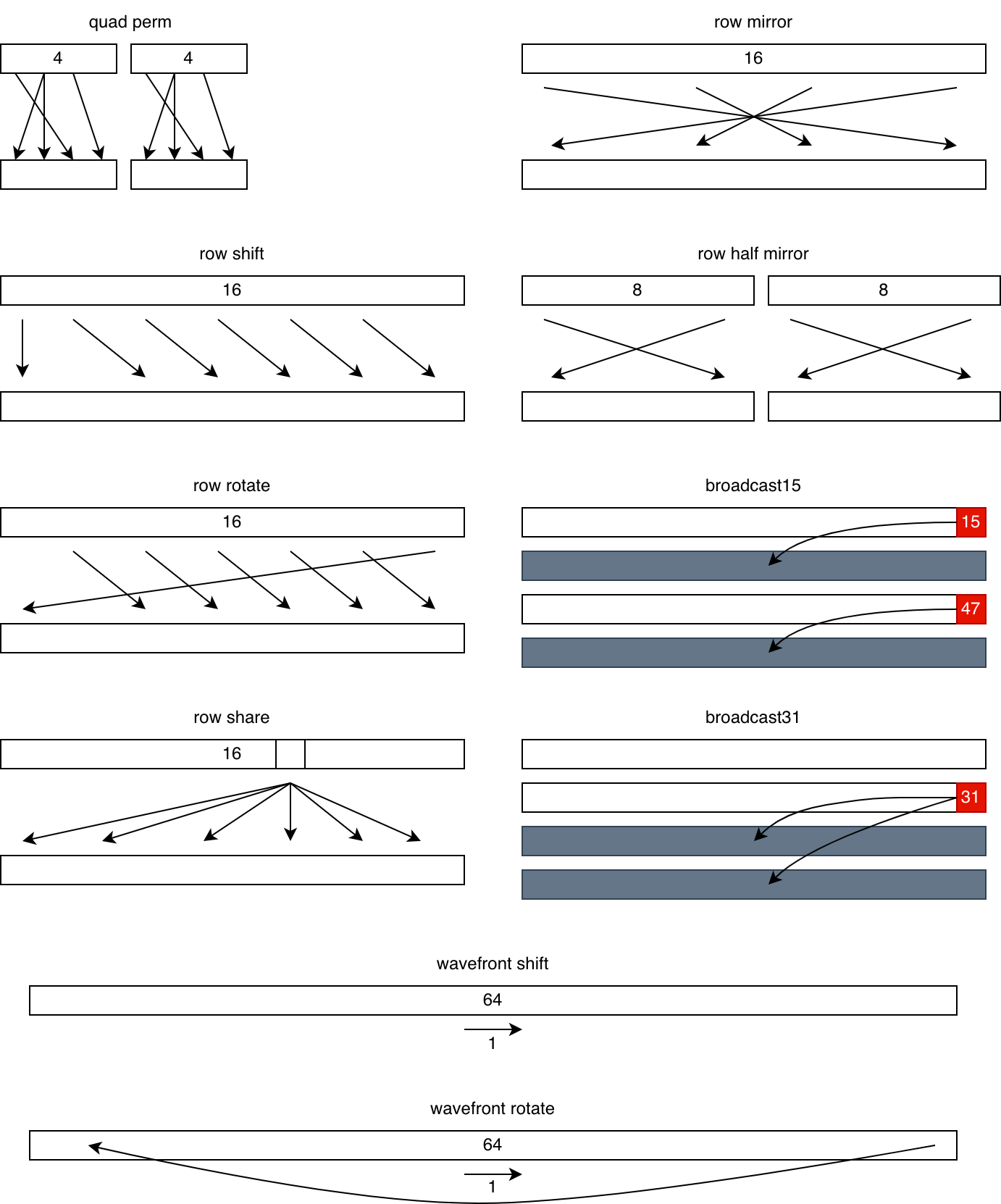

Other patterns supported by DPP include:

- quad perm: do an arbitrary permutation within each group of 4 consecutive lanes.

- row shift: Shift each chunk of 16 right/left by 1-15 lanes. The first/last few lanes are unaffected.

- row rotate: Similar to the above, but with wraparound

- row share: broadcast a specific lane to its entire row

- row mirror: reverse each row

- row half mirror: reverse each octet

- wave64 only:

- broadcast15: broadcast the last lane of each row to the entire next row

- broadcast31: broadcast the last lane of the first half to the entire second half

- wavefront shift: shift the entire wavefront right/left by 1 lane. the first/last lane will read its old value.

- wavefront rotate: like the above, but the last lane's data goes to the first lane (or vice versa)

We've taught the SCALE compiler to recognise if a shuffle matches any of the DPP patterns and generate the appropriate variant when possible. In cases where no DPP pattern matches, SCALE will fall back to using bpermute.

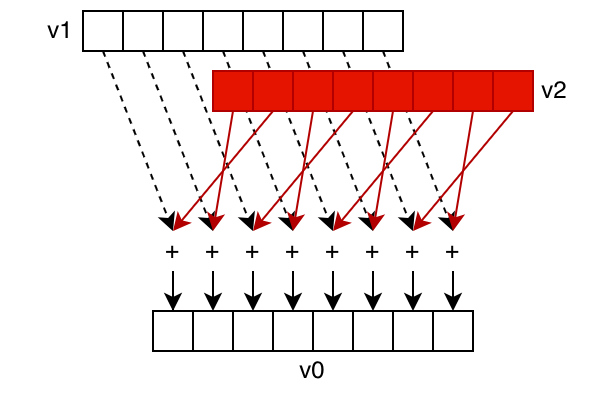

shuffles for free: fusing shuffles into other operations

Since DPP isn't an instruction, it can be fused into other operations. If you want to shuffle some data, then pass the result to another operator, you can do both with just one instruction.

The reasons that DPP is so much faster than bpermute are:

- DPP can be merged with another operation (like an add), whereas

bpermutecannot. bpermuteuses the shared memory cache, which will be very busy in real applications that use shuffles. This means that we can expect worse latency from bpermute in real programs that are doing shuffles.

As an example, consider v_add_u32_dpp v0, v1, v2 quad_perm:[2,3,0,1]. Here, v0/v1/v2 are "vector general purpose registers" which are basically registers with a separate value for each thread. Thread 0's v0 is separate from thread 1's v0. This instruction first shuffles the contents of v2 according to the pattern quad_perm:[2,3,0,1], then adds it with v1 and stores the result to v0.

Optimizing complex shuffles

When a single shuffle primitive is not enough, SCALE combines multiple instructions to build the required permutation efficiently.

Optimization through sequences of DPP operations

Some common shuffles can't be represented by a single DPP operation, but could be implemented with a sequence of multiple DPP operations that implement the equivalent permutation. Doing a few DPP operations is still more efficient than a single bpermute.

For example, the XOR pattern isn't supported on all architectures, but we can build it using a combination of quad perm, row mirror, and row half mirror. Here's how we would do XOR 5:

Optimizing more complex patterns through swizzle and permlane

AMD GPUs also offer other fast mechanisms for doing permutations that were not commonly exploited prior to SCALE, such as swizzle and permlane. In general, these mechanisms are a middle ground between bpermute and DPP: faster than bpermute, but slower than DPP. They can handle some permutations (for example, a pattern commonly used in FFTs) that are not otherwise representable with DPP.

Reductions

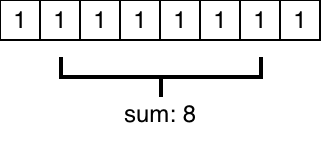

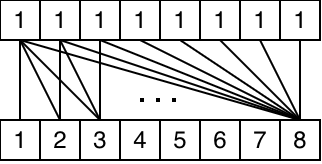

Two of the most common tasks done with CUDA shuffles are reductions and scans (aka cumulative sums).

A reduction is a fold over a certain operator over a list of items, like taking the sum of an array.

A scan computes the reduction of all previous lanes for each lane.

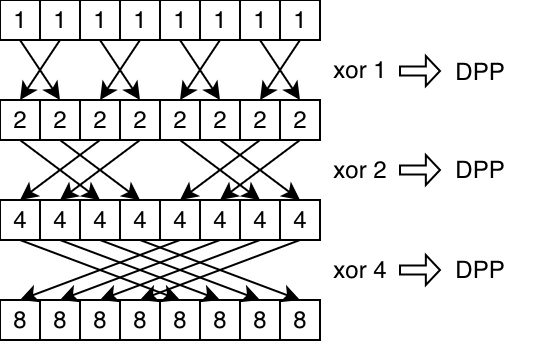

CUDA has reduction intrinsics, such as __reduce_add_sync. But users can also write their own, using a sequence of shuffles. For example:

int acc = in[laneIdx];

for (int offset = 1; offset < warpSize; offset *= 2) {

acc += __shfl_xor(acc, offset);

}

An important insight is that if the user wants to compute a reduction, they can write this in multiple ways. They can do it using what's called a "butterfly reduction", a sequence of xors (like the code snippet above). Or they could do a scan instead, using a sequence of shifts, and extract the value from the last lane. They might even use PTX asm!

The shuffle optimisations we have been talking about certainly help with reductions and scans, since they are made of shuffles. But we may miss some opportunities to optimise if we only look at each step in isolation. This is because some sequences have individual shuffles that cannot be done by any of the more specialised hardware instructions, only bpermute. In the second sequence above, the shifts cannot be lowered to DPP. But if we know the overall result is a reduction, we can generate a completely different sequence of shuffles – where each one can be lowered to an efficient hardware instruction – whose overall effect is the same.

So we made the SCALE compiler even smarter: it can now recognise the shape of reductions or scans. Regardless of how the user writes the reduction, the compiler will know what they're trying to do and generate the optimal sequence of machine instructions.

Conclusion

By optimizing one of the most commonly used instructions in real CUDA code, SCALE can significantly improve performance of existing CUDA code. We are (to our knowledge) the only compiler that uses DPP operations on AMD GPUs. Upstream LLVM is aware of these instructions, but does not ever generate them!

This topic on shuffles is just one data point of a larger pattern we've observed: AMD GPUs are not constrained by the hardware, but the software. Hence our philosophy at Spectral: you can do amazing things with compilers. AMD's hardware is great and has the ability to achieve high throughput, but the bottleneck is the software.

The original developers of CUDA realised the importance of software nearly two decades ago, and the importance of developing software that is able to fully leverage the underlying silicon. This has led to the mature, user-friendly platform that we see in CUDA today. In contrast, until the release of SCALE, AMD GPUs have had so much underutilised potential.

While CPU compiler engineering is a mature field and optimisations have been deeply explored, GPU compiler work is still relatively new. SCALE is full of novel optimisations which (to our knowledge) are not found anywhere else.